cycle of flowers

I intend this work to be read as an altar to look into the significance of menstruation, in order to open relevant conversation. Beginning by analysing the Lillies as a metaphor for;

Westernised ideas of femininity, to open the discussion of internalised colonialism and how that has destructed cultural significance of mensuration. Particularly in Māori culture where the coming of ones period was seen as sacred. Te Awa Atua, the divine river, carves a direct connection to Whakapapa and Papatūānuku and all the beauty that fertility has brought.

Purity brings links to sacredness by focusing on the colour white. Linking to the stark whit, chemically bleached cotton pads and tampons we see in commercialised perspectives of periods. Creating a great contrast to the traditional cloth or Angiangi that women once used. This comes from period blood being made semi-medical, and the commercialisation of period products.

As well as representing a visual connection to the female reproductive system. Leading into the use of blood, connecting the metaphorical concepts held in the Lillies with menstruation. Using the image of the blood dripping as a comment on fluidity. Including that of gender transition or identification, for whom this topic can be hurtful and must be considered with respect and patience. Creating a visual key for Te Awa Atua by the flow of the blood, which has been been imagined as an ancient river carrying life, past and present.

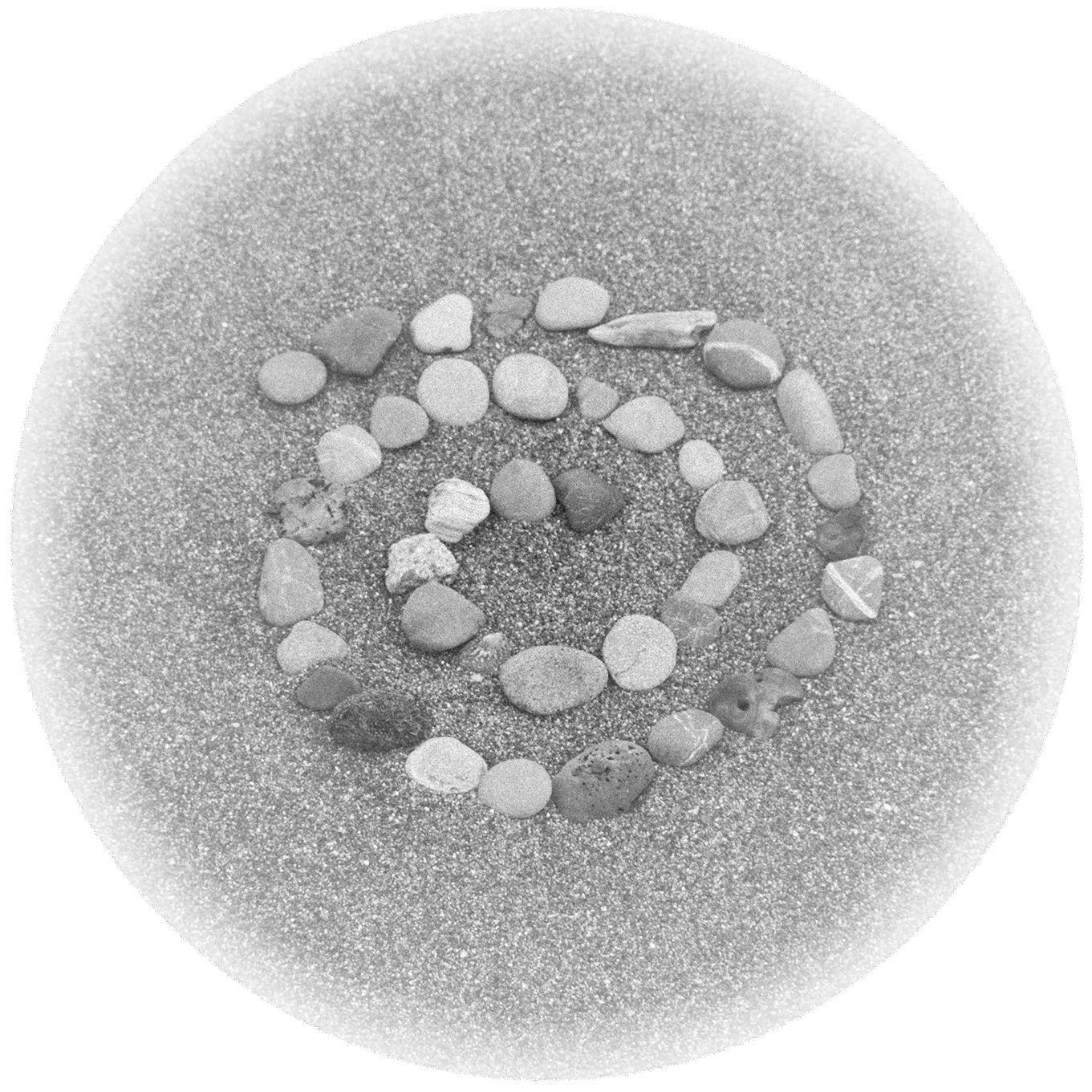

In making the sheet, which is representative of the 28 days in the average menstrual cycle, I exposed 28 images of hands washing a sheet. As washing blood from a sheet is heavily repeated and almost ritualistic throughout ones menstruating years. This is brought out in the old blood stains made visible from this cyanotype process.

Using sequencing to represent the different fractions of the menstrual cycle, starting at 12 o’clock, the hands are scrubbing the sheet, representing the period and the cleaning that often takes place here. Following until 2-3 o’clock where the hands begin to transition into a loosening, or sorting of the sheet to represent ovulation. With a single image being the sheet without hands to signify the middle of the optimum ovulation period. At 7pm there is another transition into the wringing out of the sheet, identifying the thickening of the uterine lining. Until it meets at 12 o’clock, having completed an entire circle.

Not only was the sheet originally photographed in the washing, it was then washed again multiple times during the cyanotyping, bleaching and toning process. It was then hung to present these photographs, creating yet another circle of life within the project.

This project was formed around conversations with relevant people from Pōneke, Wellington’s community, to open the conversation about menstruation. By welcoming everyone to understand menstruation, it will become safer, opening space for more accessible resources and knowledge to be shared and received.

2020.

1 Dr Ngahuia Murphy, “Welcome to Waiwhero,” Waiwhero. https://waiwhero.com 2 Angiangi is an absorbent gauze like moss that was a tradition Māori solution to dealing with menstrual blood. See: http://weloverongoa.co.nz/glossary/ 3 Quote by Robyn Goldsmith, of Wellington Women’s Health Collective. 4 Leonie Hayden, Michele Wilson, Dr Ngahuia Murphy, "The hilarious, stressful, hidden world of menstruation | On the Rag: Periods (full episode” 5:30-11:00. On The Rag. Auckland, New Zealand. https://thespinoff.co.nz/video/on-the-rag/?post_id=231240 5 Office of Women’s Health. “Menstrual Cycle Tool.” Womenshealth.Gov, 16 Mar. 2018, www.womenshealth.gov/menstrual-cycle/your-menstrual-cycle All blood in the making of this work was collecting from my menstruation, using a menstrual cup made by Wā collective.